In college, I took a philosophy class (loved it, even though it made my head hurt), and we studied the “brain in a vat” theory, the idea that we are simply brains floating in some substance who think we are people but really don’t have bodies or do things. It’s a strange idea, even just writing it out messes with my head. But I think of that concept often because in a lot of books I read for first-time novelists and memoirists, I find a lot of thinking and talking but very little doing or moving and sometimes almost no setting. It’s kind of like reading a book where the characters are brains in vats . . . and as you can imagine, that’s not only hard to imagine but also pretty boring.

You’ve Got to Move It, Move It

People move. It’s part of what defines what it is to be a an animal – movement. (And yes, some plants move, but let’s leave the venus flytraps out of this, okay?) Yet, often, when we write dialogue – I’ve done it, too – we have two or more people in conversation without any movement at all. It’s as if they are completely still just talking at one another. It’s kind of creepy to picture.

People move when they talk. Their faces move maybe – a twinge of the eye, a curl of the mouth, a flare of the nostrils (although be sparing with this one lest your character seem like a bull in a ring). Or maybe they talk with their hands. Maybe their feet fidget or they are a knee-bouncer. (I was one of those ALL through school. I hereby apologize to anyone who sat near me.)

And the way people move tells us something about the person who is moving. If the eyes of the woman in the wheelchair get very wide when another woman walks into the art gallery, that tells us something that we can elucidate further. Is she afraid? Surprised? Angry? Her eyes tell us to pay attention.

The movement also tells us something about the relationship between people. Does the first partner in the couple lean in when the other partner speaks while the other leans out? Or does that mother reach under the table to still her bouncing daughter’s knee during dinner with the admissions’ counselor? Those movements matter, and they help describe relationships in a precise, efficient way.

Where in the World?

The second thing I often find missing in narrative – fiction or nonfiction – is lack of a place for the scenes. Sometimes the world-building is amazing. I can know it’s 1922 in an alternate reality where Hong Kong is Hong Kong but with monkeys, and yet, when two of the monkeys start talking, I have no idea where we are. We could be in a fine restaurant on top of a skyscraper or in a sewer tunnel a la those mutant turtles. It’s as if these voices are speaking into the ether.

Put your characters somewhere for every scene, and gives us the details of that place. Think of all five senses, and as appropriate, incorporate each of them. Tell us what the characters touch, hear, taste, smell, and see (if your characters have the use of all five senses, of course), or note what isn’t there, especially if a particular missing element is telling to the story. Use the place to create atmosphere, absolutely, but also think about how it might help further the narrative itself.

In short, the only time your characters should be completely still and without a place is when they are unconscious and floating in space. If they are doing the George Clooney in Gravity and floating off to their death, it’s totally fine for them to be still and in a void. Otherwise, move them around and give them a location. No brains in vats, please.

**

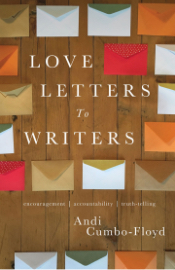

Just a quick update on my quest to sell 1,000 copies of Love Letters To Writers by year’s end. As of Tuesday afternoon, I have sold 268 copies, so still not at a third of my goal. I’m going to be making a plan in the next week to up that number substantially by the end of September, so stay tuned in two weeks for more info. But the good news is that Love Letters To Writer: Volume II will be out in November, and I’m so excited. More on that soon, too.

Just a quick update on my quest to sell 1,000 copies of Love Letters To Writers by year’s end. As of Tuesday afternoon, I have sold 268 copies, so still not at a third of my goal. I’m going to be making a plan in the next week to up that number substantially by the end of September, so stay tuned in two weeks for more info. But the good news is that Love Letters To Writer: Volume II will be out in November, and I’m so excited. More on that soon, too.