If you know my work, you know I have a deep commitment to telling the long-hidden stories of enslaved people here in the U.S. So today, I am deeply honored to share the story of Brian C. Johnson and his beautiful, powerful book, Send Judah First. May you find inspiration and courage for your own words here.

I’ve only been writing fiction for a short while—about ten years. That is two novels. I never imagined writing novels at all. Several years ago, our local newspaper was doing a special pullout magazine for Black History Month. The focus was to be “African-American artists in the Valley.” The reporter identified me as an artist. When I mentioned that I didn’t do any art, she questioned, “Aren’t you a writer?” That is was not an identity I had ascribed to myself. “Me, a writer?” I explained I had not written anything other than a few lovelorn, sappy poems only my girlfriend would see and a couple plays I hoped would be performed in church.

A few months later, she invited me to join her in the NaNoWriMo Challenge. I took her up on it. I had virtually no idea how to write a novel, but I had always heard that you should write what you know. As the first of November loomed, I had little idea what I would write about—until I experienced a very vivid dream; the dream stayed with me, almost haunting me. I knew that was to be the novel. I won NaNoWriMo that month—in 26 days. It took me another eight years to get it ready for publication. Titled, The Room Downstairs, my debut novel released in 2016, much of it was my childhood memories realized.

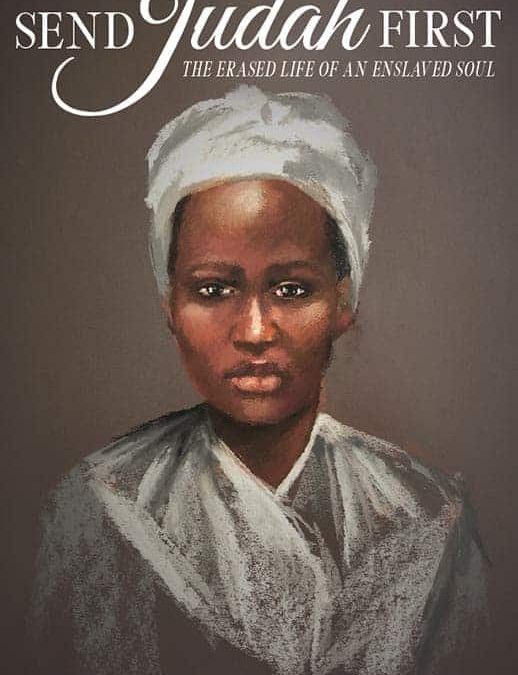

My sophomore novel, Send Judah First: The Erased Life of an Enslaved Soul, launched in August 2019. I first “met” Judah on Saturday, October 16, 2016. As part of my responsibilities as director of the Frederick Douglass Institute for Academic Excellence at Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania, I led an overnight student field trip for a living history weekend at Belle Grove Plantation in Middletown, Virginia.

After disembarking from the bus, our guides led us to the plantation’s winter kitchen, a lower level room with a big fireplace. A woman dressed in period attire stirred pots hanging in the fireplace, preparing our dinner. Kristen Laise, executive director of the plantation, introduced Ranger Shannon Moeck of the National Park Service, who would tell us more about the woman who had occupied that space for over two decades in the early 1800s.

The program was titled “Kneading in Silence: A Glimpse into the Life of Judah the Enslaved Cook.” Ranger Moeck provided an overview of the laws governing life of the enslaved in Virginia and spoke of Judah’s children.

We were told about the multi-layered work of the enslaved cook, who not only prepared the food for the master and his family, but also for all the enslaved workers. I felt a kinship to Judah. I love to cook. We were encouraged us to “imagine life for Judah and her family at Belle Grove . . . years of working, living, raising a family under enslaved conditions.”

And then came a detail that nearly broke my heart—there are only two existing documents that prove Judah ever lived. Sitting in her kitchen, I made a promise to Judah that I would not let her be forgotten. I would tell her story. I would share her forgotten, lost voice with the world.

The first challenge I faced in writing Judah’s story was internal. As an avid reader of narratives of the enslaved, I felt intimidated by Alex Haley’s Roots. The book, turned TV miniseries, stands at the pinnacle of slave narrative literature and media. I wrestled with not wanting to compete with Haley. Similarly, Twelve Years a Slave, by Solomon Northup has captured contemporary thought about plantation life. As a neophyte writing historical fiction, I wondered if I had the mustard to be able to tell the story.

Externally, there has been a lot of discussion in the modern press and on social media about how audiences are tired of seeing “black people in pain” [poverty, slavery, drug addiction and crime]. With this in mind, I wondered, what can I write that’s new? That is why I introduced a love story of sorts. Judah was forced to marry Anthony, perhaps for capitalistic reasons on the part of Master Hite. But, in time, she grows to love him and wanted to create a life with him (despite the circumstances). That is a side we hardly ever get to see.

Almost three years after being introduced to Judah, we launched Send Judah First, from Belle Grove’s kitchen. As I drove down the tree-lined lane towards the manor house, I whispered to Judah, “I’ve kept my promise.” It pains me to think there are so many millions of people who will go unnamed, unremembered, glossed over simply because someone decided to slap the label SLAVE on them. U.S. history is full of these hard truths that needs to be shared and confronted, and “hard history” is what inspired me to pursue Judah’s story, and share it with the world.

In 2019, we, as a nation, celebrate, mourn, and acknowledge the 400th anniversary of the first arrival of Africans as slaves to Virginia. America must grapple with this “hard history.” Twelve of our early presidents were slave owners. President James Madison, chief author of the document declaring America’s commitment to equality called slavery, “the most oppressive dominion ever exercised by man over man.” By the way, President Madison saw blacks as three-fifths of a human (for census purposes). Madison makes an appearance in Send Judah First, as he was the real-life brother of Nelly Madison Hite, first mistress of Belle Grove.

I am deeply indebted to the staff at Belle Grove who were committed to seeing Send Judah First completed. Having research partners is essential to writing a good piece of historical fiction. Belle Grove is not hiding from its past. They were happy to work with me, answer questions, and help to tell give historical basis for Judah’s story.

My next NaNoWriMo project will again take me down a historical fiction path, force readers to confront “hard history”, as I tell the story of Caesar Blackwell, an enslaved preacher from Montgomery, Alabama.

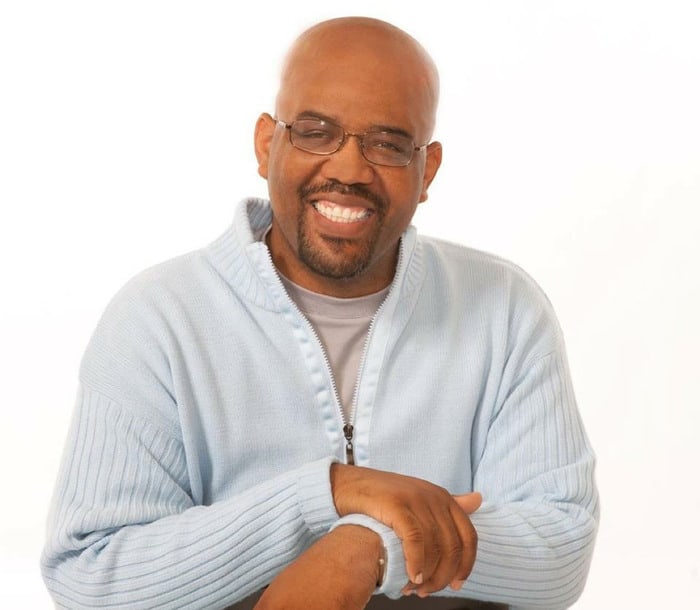

Brian C. Johnson honors the struggles and accomplishments of the ordinary citizens who launched the Civil Rights Movement by committing himself personally and professionally to the advancement of multicultural and inclusive education. He has served as a faculty member in the department of academic enrichment at Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania and was the director of the Frederick Douglass Institute for Academic Excellence. He is a founder of the Pennsylvania Association of Liaisons and Officers of Multicultural Affairs, a consortium that promotes best practices in higher education. He earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English from California University of Pennsylvania and a PhD at Indiana University of Pennsylvania in Communications Media and Instructional Technology. His research examines the role of mainstream film in the development of social dominance orientation.

Brian C. Johnson honors the struggles and accomplishments of the ordinary citizens who launched the Civil Rights Movement by committing himself personally and professionally to the advancement of multicultural and inclusive education. He has served as a faculty member in the department of academic enrichment at Bloomsburg University of Pennsylvania and was the director of the Frederick Douglass Institute for Academic Excellence. He is a founder of the Pennsylvania Association of Liaisons and Officers of Multicultural Affairs, a consortium that promotes best practices in higher education. He earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English from California University of Pennsylvania and a PhD at Indiana University of Pennsylvania in Communications Media and Instructional Technology. His research examines the role of mainstream film in the development of social dominance orientation.